What Jane Austen Saw: Nature, then and now

An exploration of British wildlife since the birth of Jane Austen

In the run up to this year’s Earth Day (22 April) I’d been thinking a lot about the impact of climate change and biodiversity loss on the places I enjoy. Sometimes it can be difficult to really comprehend what that means on a practical level. After all, I don’t really see any biodiversity loss - yes, when I was young and we used to go on drives the car windscreen would be splattered with insects, whereas nowadays there’s barely a squashed gooey smudge to be seen on my car (this is called the ‘Windscreen Phenomenon’ apparently), but I still hear birds, and I still see wild animals and flowers when I’m out and about. How bad is it, really? Somehow it doesn’t seem all that different compared with my hazy recollections from childhood.

And that’s when a throw-away comment from a friend opened my eyes. She mentioned that the baseline most of us use - our own lifetimes - is simply too short to really see the whole picture. We need to step back and widen the focus to show the whole timeline from the Industrial Revolution to now to avoid being, as ecologist Isabella Tree says, ‘blinded by the immediacy of the present.’

Jane Austen was born in 1775, right back at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution - that mammoth tidal wave of technological change that spread from the UK across the world. Surely then comparing the environment and natural world from her life to mine might give me a clearer picture and help me to avoid the Shifting Baseline Syndrome that I’ve been prone to for so long?

And so I dived in.

And it turned out that when Austen stepped outdoors she would have seen and heard a much more colourful, noisy world.

‘I walked to Alton, & dirt excepted, found it delightful.’

(Jane Austen to Cassandra, Feb 1813)

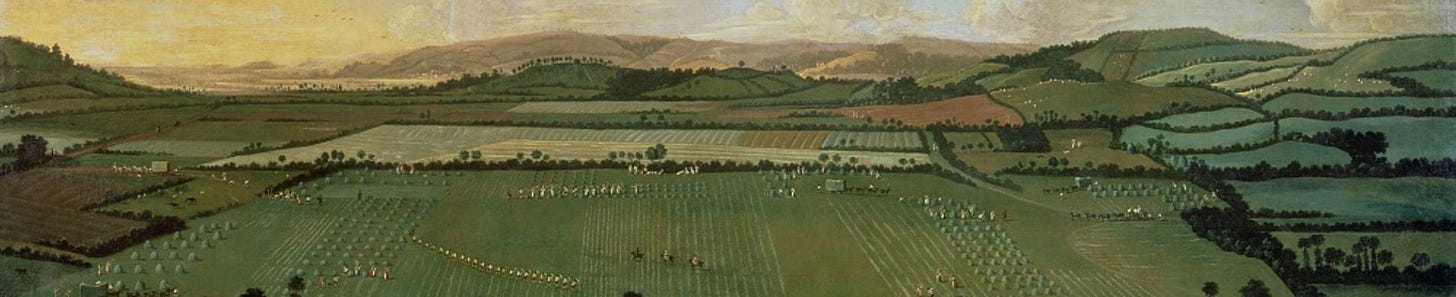

One difference she’d have seen was in how the land was being used. For example she’d have regularly walked past beautifully rich hay meadows brimming with wildflowers and insects (over 97% of wildflower meadows have been lost since the 1930s1). Hay meadows were a vital part of the farming landscape. These grasslands were left wild until summer when the community cut and stored the hay to use as animal feed during the winter months.

The sheer number of native wildflowers and plants Austen would have seen, in these hay meadows and also throughout the landscape, would have been significantly larger than the numbers we see today (half of our native plants have declined over the last 20 years2). Unbelievably, there are now more non-native species than native growing in Britain.3

Another obvious change, that many of us will be aware of of, is the enormous decline in elm trees. This lofty tree used to dominate the landscape but sadly since the 1960s it has been decimated by Dutch elm disease and is now a rare sight, although there are currently breeding programmes of new disease-resistant hybrid varieties.

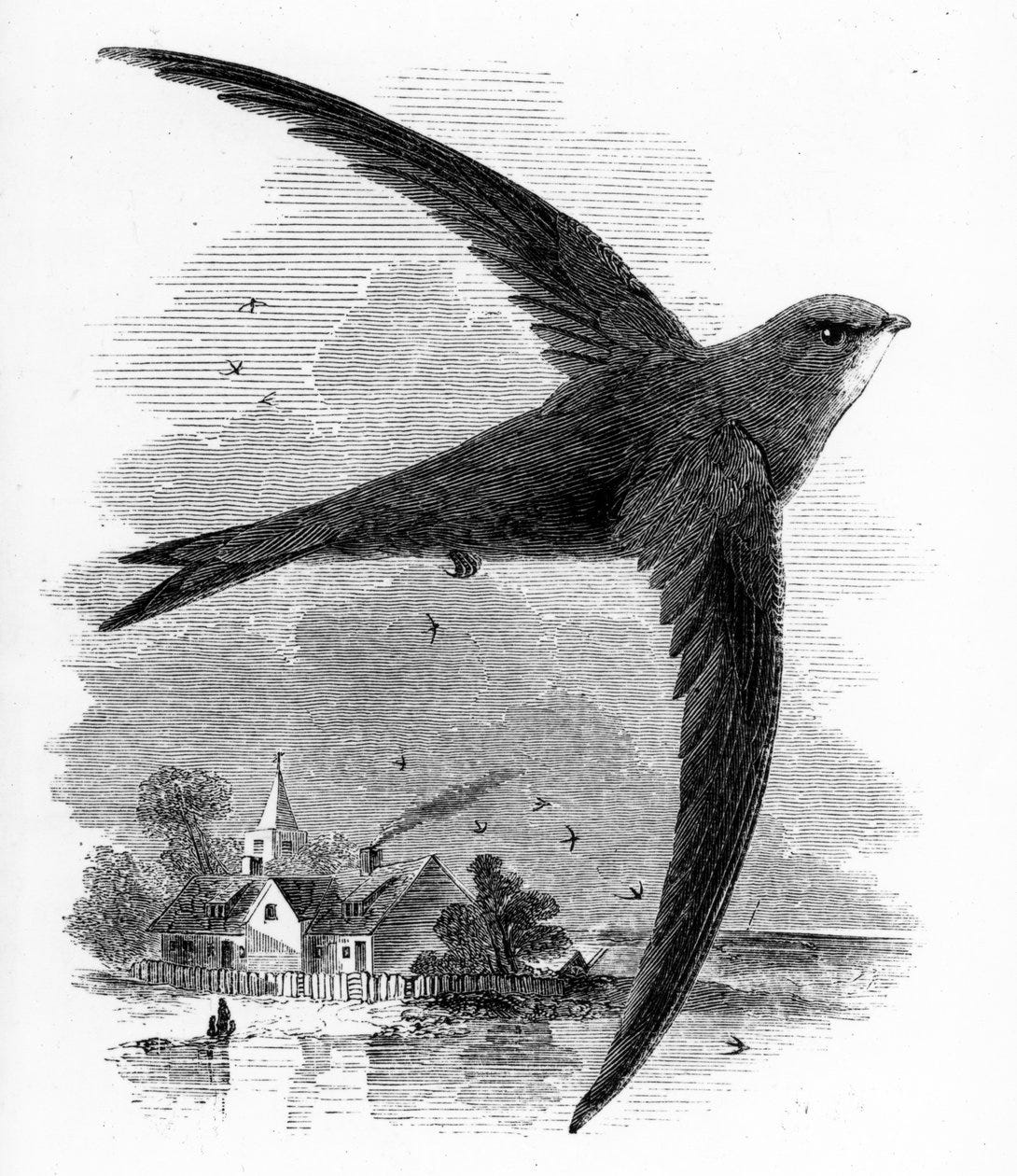

Furthermore, the number of birds was dramatically higher when Austen walked through fields and down lanes. Unlike me, she’d have frequently heard the soft call of cuckoos, the evening song of nightingales, and the lively trill of wood warblers (cuckoo numbers have dropped by 65% since the early 1980s; nightingale numbers plummeted 90% between 1967 and 2022; wood warbler numbers have fallen 81% in the last 30 years; and almost half of all UK bird species are in decline4). In the skies above her, she’d have seen multitudes of swifts (swifts have decreased by two-thirds since 19955), scores of lapwings, and flights of graceful swallows.

Austen contemporary and ‘parson-naturalist’ Gilbert White of Selborne in Hampshire (close to Chawton where Austen lived) wrote in his diary in July 1786:

‘A cloud of swifts over Clapham: they probably have brought out their young.’ (Gilbert White, Jul 1786)

I love this description - he saw so many swifts flying together that the best collective noun he could ideate was ‘cloud’. (Incidentally in the same entry White goes on to say that ‘on this day Thomas got up all my hay in good order, & finished my rick’ so even curates could have their own hay meadows.)

Flying insects would have likewise been significantly more abundant in Austen’s time, with many more bright butterflies and dusky moths than we see today (half of British butterflies are on the extinction Red List,6 and flying insects have decreased by 60% over the last 20 years7).

British mammals that Austen would have seen many more of include bats, red squirrels, water voles, and hedgehogs (many species of British bats, as well as water voles and hedgehogs are now on the ‘near threatened’ or ‘near extinction’ Red Lists8 and native red squirrels have long since been pushed out of most of England by North American grey squirrels that were introduced in the 1800s).

In fact it turns out that the UK has lost around half of its biodiversity since the Industrial Revolution, and damningly we’re in the bottom 10% of all countries globally, which I suppose sadly makes sense considering it all started here.9

And lastly, a warming climate means that spring in England starts around a month earlier than Austen would have been used to,10 and in autumn she would have seen the trees lose their leaves earlier than they do today.

So all things considered, the English countryside around me seems sadly different since Austen’s birth.

But there is good news. There are lots of successful projects bringing back threatened species and increasing local biodiversity.

In Selborne, Gilbert White had recorded in 1787 how the swifts used to nest in the eaves of the ancient church, but by the early 2000s they were long gone. However the charity Hampshire Swifts has worked in partnership with the church to install nesting boxes and has successfully encouraged the swifts back.

And this is just one of many similar projects. And as individuals we can all help too - from planting native flowers in our gardens to doing No Mow May, or from leaving weeds, long grass, and twig and leaf piles, to putting out a dish of water for thirsty hedgehogs on hot days. There are also loads of great books full of rewilding ideas available to give us inspiration and ideas.

‘Rewilding shows us that nature bounces back incredibly quickly if you let it. That it's really forgiving, and I think that's a galvanising message; a message of hope.’

Isabella Tree

Yes, Austen’s countryside was much more biodiverse, but learning what she’d have seen and heard that I don’t, has galvanised me to take positive action, and make changes in my garden and in my community to increase those missing and threatened species and encourage nature to come back.

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/nationally-important-wildflower-grasslands-get-increased-protection

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/mar/08/half-of-britain-and-irelands-native-plants-have-declined-over-20-years-study

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2023/march/over-half-britains-plant-species-now-non-native.html

https://www.bto.org/our-science/projects/breeding-bird-survey/research-conservation/cuckoo-decline

https://www.birdguides.com/articles/conservation/uk-common-nightingale-decline-linked-to-winter-habitat-quality/#:~:text=Fieldwork%20has%20shown%20that%20the,since%201967%20(Nick%20Appleton).

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2023/april/almost-half-of-all-uk-bird-species-in-decline.html

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2024/may/third-surveyed-uk-bird-species-declined-since-1990s.html

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2022/may/half-british-butterflies-placed-extinction-red-list.html

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2022/may/uks-flying-insects-have-declined-60-in-20-years.html

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/oct/28/hedgehogs-near-threatened-red-list-decline-over-past-decade

https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/mammals/water-vole#:~:text=Conservation%20status&text=Water%20voles%20are%20listed%20as,England%20Red%20List%20for%20Mammals

https://www.bats.org.uk/about-bats/threats-to-bats

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2020/september/uk-has-led-the-world-in-destroying-the-natural-environment.html

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/spring-in-the-u-k-arrives-a-month-earlier-than-in-the-1980s/